| "The common grunt doesn't give a

damn about purposes and justice. He doesn't even think about that shit. Not when he's out

humping, getting his tail shot off. Purposes - bullshit! He's thinking about how to keep

breathing. Or he wonders what it'll feel like when he hits that booby trap. Will he go

nuts? Will he puke all over himself, or will he cry, or pass out, or scream? What'll it

look like - all bone and meat and pus? That's the stuff he thinks about, not

purposes." (p. 178). |

|

|

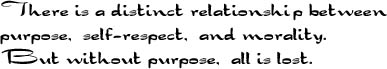

"Does not purpose reflect on

self-respect? Does not the absence of good purpose jeopardize the soldier's own ego, thus

making him less likely to fight well and bravely? If a war is without justice, the soldier

knows that the sacrifice of life, his own valued life, is demeaned, and therefor his

self-respect must likewise be demeaned." (p. 179). |

| "In war one nation is able to make

up for production insufficiencies by calling on the industrial capacity of allied nations...By

citing a great moral purpose, Britain was able to generate American industrial aid to

defeat the Germans. In comparison, Germany and Japan were left virtually without allies.

Unable to summon other nations to their cause, because, in fact, they had no just cause.

So in the end it was an absence of clear moral purpose that produced defeat." (p.

177). |

|

|

"Not because of strong convictions,

but because he didn't known. He didn't know who was right, or what was right, he didn't

know if it was a war of self-determination or self-destruction, outright aggression or

national liberation; he didn't know if nations would topple like dominoes or stand

separate like trees; he didn't know who really started the war, or why, or when, or with

what motives; he didn't know if it mattered; he saw sense in both sides of the debate, but

he did not know where the truth lay; he simply didn't know. He just didn't know if the war

was right or wrong or somewhere in the murky middle. So he went to war for reasons beyond

knowledge. Because he believed in law, and law told him to go. Because it was a democracy...He

went to war because it was expected. Because not to go was to risk censure, and to bring

embarrassment on his father and his town. Because, not knowing, he saw no reason to

distrust those with more experience. Because he loved his country, and more than that,

because he trusted it. Yes, he did. Oh, he would rather have fought with his father in

France, knowing certain things certainly, but he couldn't choose his war, nobody

could." (p. 234-235). |